Killing Orcas

Killing Orcas

Orca. Killer whale. Seawolf. Blackfish. Whatever you call this magnificent mammal, it is undoubtedly the most beloved icon of Pacific Northwest waters. The orca is a true apex predator as it has no natural enemies. Despite this grand stature, the Pacific Northwest orca is now endangered and has become one of the most toxic mammals on the planet.

The Magnificent Killer Whale

The killer whale is actually not a whale but the largest member of the dolphin family. The largest recorded orca measured 32 feet in length and weighed over 8 tons. More typically, adult males range from 19-26 feet in length and weight up to 6 tons while females range from 16-23 feet in length and weigh 3-4 tons. Adult males are easily distinguished in a pod as their dorsal fins are about twice the height of their female counterparts. Male orcas tend to live about 25-50 years, while females can live 70 years or longer. The matriarch of K-pod recently died when she was 98 years old. Although killer whales roam all four oceans and are the most widely distributed cetacean, they favor cooler and even polar waters. The world-wide population of Orcas is somewhere around 50,000 animals.

Orcas are very intelligent creatures as evidenced by their highly organized social structure based around a single matriarch. The matriarch leads her pod consisting of her descendents, both male and female. The pod often stays together for life. Breeding does not take place within the pod - pods intermingle to reduce the risk of inbreeding.

Orca social structure is very tight and orderly. Orcas do not appear to fight amongst themselves. They share food with one another, attempt to care for their sick, and even “baby sit” each others offspring. They only kill animals they consider a food source, although they don’t always eat their kill. There is no record of a wild orca intentionally killing or even attacking a human.

Orcas are vocal animals and rely heavily on acoustics. They use a multitude of whistles, pulses calls, and clicks. Clicks are used for echolocation purposes to find food and distinguish objects underwater. Whistles are usually a continuous tone that may last for many seconds. Pulse tones are used as the orcas main form of communication with one another. Each pod develops its own pulse tone dialect. Closely related pods have dialects with more in common than pods that are more distantly related. Orca dialects are believed to be a learned skill (as opposed to intuitive), as mothers have been witnessed using simplified pulse tones when communicating with calves. Marine biologists have studied these dialects and can determine relationships between orca pods based upon dialect similarities. Pods are determined to be part of the same clan if the pods share common calls.

Orca pods live one of three lifestyles - resident, transient, and offshore. As the name implies, residents stay in a relatively confined geographic area and specialize in hunting fish. Transients roam much larger geographic areas and specialize in hunting marine mammals. Transients orcas have sharper dorsal than their resident cousins. Offshore orca population stay in deep open waters, so not much is known about them. These social classes do not intermingle - in fact they go out of their way to avoid each other. Even clans within the same social class sometimes avoid each other.

Another interesting note is that resident orcas are much noisier that transient orcas. The reason for this is believed to be that marine mammals have better hearing than fish, so the transients must remain quite when hunting so as not to give away their presences.

Local Orca Populations

The Pacific Northwest is blessed with both transient and resident orca populations. An entire industry of whale watching in the Pacific Northwest is built around these orcas and migrating grey whales during summer months in the San Juan Islands. Although transient ocras come and go at random, local resident populations make regularly scheduled appearances in our waters. Three communities of orcas are commonly found in Pacific Northwest waters - northern residents, southern residents, and transients. Our local orcas were heavily targeted for captured by marine parks in the 1960s and 1970s. Approximately 70 animals were removed from our local resident populations, with the southern residents being hit the hardest. Orcas are now protected from capture in Pacific Northwest waters.

Individuals orcas are readily identified by the characteristics of their dorsal fin and the light colored patch (called a saddle) immediately behind the dorsal. All resident orcas in the Pacific Northwest are identified, named, and monitored by various organizations.

Southern Residents

The southern residents are the best known and most studied of our local orca populations. This population represents one clan (J Clan) consisting of three different pods, (J, K, and L pods). J-pod contains about 40 members; K- and L-pods about 20 members each. The southern resident population at the end of 2008 was 83 members. This population was recovering nicely until 1995. Since 1995, a number of sudden and unexpected deaths have reduced the southern resident population from about 98 to the currently level of 83. In 2008 alone, J-pod was stricken with seven unexpected deaths. Most of the deaths involved juveniles, which is very concerning. However, more concerning is two of the deaths were mature females of breeding age.

The southern residents typically spend summers around Victoria and the south side of San Juan Island feeding on returning chinook salmon. The pods of the southern residents have been known to venture as far north as the Queen Charlotte Islands and as far south as California. The southern residents were listed as an endangered species in 2005.

Northern Residents

The northern residents are a bigger community than their southern counterparts. Northern resident populations have steadily increased to 220 members through 1999, then decreased by about 10%, but have since rebounded. The northern resident population is made up of 3 clans (A, G, and R Clans), representing 16 pods and 33 matrilines. The northern residents live primarily in the more pristine waters around the north end of Vancouver Island, but have been known to venture into SE Alaska.

Transients

As their name suggests, transient orcas come and go at will. They range the entire west coast, from California to Alaska. These orcas are specialized in hunting marine mammals. A transient population entered Hood Canal for several weeks a few years ago and hunted seals. One estimate I saw is the transients thinned out the Hood Canal seal population by about one third before leaving. Although this may seem brutal, these types of events are important to keep nature in balance. Reduced seal populations give salmon, rockfish, and other species a better chance at survival.

Unlike residents, transients travel in much smaller pods - usually about five members in size. Also unlike residents, young often leave the pod after they mature. Speculation for this behavior is that hunting marine mammals requires more stealth and nimbleness than hunting schools of fish, and is therefore easier to do in a small group.

Pollution

Being a long-lived apex predator, orcas are an excellent barometer of the health of Pacific Northwest waters. The recent decline in the resident orcas populations has given rise to concern regarding how man-made toxins are affecting our local orcas.

The resident orcas feed almost exclusively on salmon. Five species of salmon frequent the Pacific Northwest. Of these species, orcas prefer the chinook salmon for several reasons. First, chinook store more fat than other salmon species, and fat = energy. Second, chinook grow much larger than their cousins. Mature chinook salmon returning to Northwest waters to spawn average about 15 pounds and can grow to over 50 pounds. Third, chinook are available in local waters year round. Chinook salmon are thought to make up about 70% of the northern residents diet, and 80% of the diet for southern residents.

Unfortunately, the high fat content in chinook is a two edged sword. Although this fat is high in energy, it is also high in toxins. Persistent organic pollutants (POPs) such as PCBs (polychlorinated biphenyls) and PBDEs (polybrominated diphenylethers) collect in the fatty tissues of animals. Once consumed by a predator, those toxins become part of that predator and generally cannot be purged. The one exception is that females are able to purge some of these toxins through their breast milk as this milk is very high in fat content.

Research has established solid links between elevated levels of POPs and cancers and impaired neurological, immune system, and reproductive development. Unfortunately, much of the salmon entering Puget Sound carry three to five times higher levels of PCBs than what is considered normal. It is even worse for PBDEs - Puget Sound salmon carry four to 28 times the PDBEs of northern British Columbia salmon. Southern resident orcas feed predominately upon these salmon and bioaccumulate the toxins from these salmon in their tissues. An indicator of the ill effects of these toxins was evident in 2000 when a 22 year old male orca from J-pod washed ashore. This animal should have been sexually mature after 15 years, but was not. Toxins are believed to have impaired his maturations process and contributed to the orcas early death.

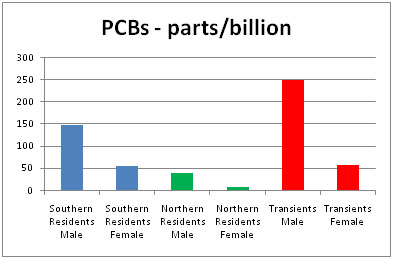

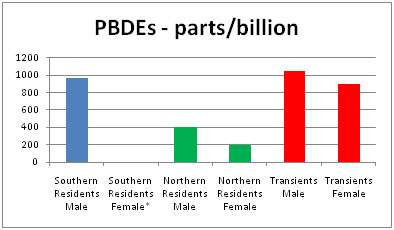

A recent study from the Canadian Department of Fisheries and Oceans indicated the following toxin levels amongst the three distinct orca communities:

The Magnificent Killer Whale

The killer whale is actually not a whale but the largest member of the dolphin family. The largest recorded orca measured 32 feet in length and weighed over 8 tons. More typically, adult males range from 19-26 feet in length and weight up to 6 tons while females range from 16-23 feet in length and weigh 3-4 tons. Adult males are easily distinguished in a pod as their dorsal fins are about twice the height of their female counterparts. Male orcas tend to live about 25-50 years, while females can live 70 years or longer. The matriarch of K-pod recently died when she was 98 years old. Although killer whales roam all four oceans and are the most widely distributed cetacean, they favor cooler and even polar waters. The world-wide population of Orcas is somewhere around 50,000 animals.

Orcas are very intelligent creatures as evidenced by their highly organized social structure based around a single matriarch. The matriarch leads her pod consisting of her descendents, both male and female. The pod often stays together for life. Breeding does not take place within the pod - pods intermingle to reduce the risk of inbreeding.

Orca social structure is very tight and orderly. Orcas do not appear to fight amongst themselves. They share food with one another, attempt to care for their sick, and even “baby sit” each others offspring. They only kill animals they consider a food source, although they don’t always eat their kill. There is no record of a wild orca intentionally killing or even attacking a human.

Orcas are vocal animals and rely heavily on acoustics. They use a multitude of whistles, pulses calls, and clicks. Clicks are used for echolocation purposes to find food and distinguish objects underwater. Whistles are usually a continuous tone that may last for many seconds. Pulse tones are used as the orcas main form of communication with one another. Each pod develops its own pulse tone dialect. Closely related pods have dialects with more in common than pods that are more distantly related. Orca dialects are believed to be a learned skill (as opposed to intuitive), as mothers have been witnessed using simplified pulse tones when communicating with calves. Marine biologists have studied these dialects and can determine relationships between orca pods based upon dialect similarities. Pods are determined to be part of the same clan if the pods share common calls.

Orca pods live one of three lifestyles - resident, transient, and offshore. As the name implies, residents stay in a relatively confined geographic area and specialize in hunting fish. Transients roam much larger geographic areas and specialize in hunting marine mammals. Transients orcas have sharper dorsal than their resident cousins. Offshore orca population stay in deep open waters, so not much is known about them. These social classes do not intermingle - in fact they go out of their way to avoid each other. Even clans within the same social class sometimes avoid each other.

Another interesting note is that resident orcas are much noisier that transient orcas. The reason for this is believed to be that marine mammals have better hearing than fish, so the transients must remain quite when hunting so as not to give away their presences.

Local Orca Populations

The Pacific Northwest is blessed with both transient and resident orca populations. An entire industry of whale watching in the Pacific Northwest is built around these orcas and migrating grey whales during summer months in the San Juan Islands. Although transient ocras come and go at random, local resident populations make regularly scheduled appearances in our waters. Three communities of orcas are commonly found in Pacific Northwest waters - northern residents, southern residents, and transients. Our local orcas were heavily targeted for captured by marine parks in the 1960s and 1970s. Approximately 70 animals were removed from our local resident populations, with the southern residents being hit the hardest. Orcas are now protected from capture in Pacific Northwest waters.

Individuals orcas are readily identified by the characteristics of their dorsal fin and the light colored patch (called a saddle) immediately behind the dorsal. All resident orcas in the Pacific Northwest are identified, named, and monitored by various organizations.

Southern Residents

The southern residents are the best known and most studied of our local orca populations. This population represents one clan (J Clan) consisting of three different pods, (J, K, and L pods). J-pod contains about 40 members; K- and L-pods about 20 members each. The southern resident population at the end of 2008 was 83 members. This population was recovering nicely until 1995. Since 1995, a number of sudden and unexpected deaths have reduced the southern resident population from about 98 to the currently level of 83. In 2008 alone, J-pod was stricken with seven unexpected deaths. Most of the deaths involved juveniles, which is very concerning. However, more concerning is two of the deaths were mature females of breeding age.

The southern residents typically spend summers around Victoria and the south side of San Juan Island feeding on returning chinook salmon. The pods of the southern residents have been known to venture as far north as the Queen Charlotte Islands and as far south as California. The southern residents were listed as an endangered species in 2005.

Northern Residents

The northern residents are a bigger community than their southern counterparts. Northern resident populations have steadily increased to 220 members through 1999, then decreased by about 10%, but have since rebounded. The northern resident population is made up of 3 clans (A, G, and R Clans), representing 16 pods and 33 matrilines. The northern residents live primarily in the more pristine waters around the north end of Vancouver Island, but have been known to venture into SE Alaska.

Transients

As their name suggests, transient orcas come and go at will. They range the entire west coast, from California to Alaska. These orcas are specialized in hunting marine mammals. A transient population entered Hood Canal for several weeks a few years ago and hunted seals. One estimate I saw is the transients thinned out the Hood Canal seal population by about one third before leaving. Although this may seem brutal, these types of events are important to keep nature in balance. Reduced seal populations give salmon, rockfish, and other species a better chance at survival.

Unlike residents, transients travel in much smaller pods - usually about five members in size. Also unlike residents, young often leave the pod after they mature. Speculation for this behavior is that hunting marine mammals requires more stealth and nimbleness than hunting schools of fish, and is therefore easier to do in a small group.

Pollution

Being a long-lived apex predator, orcas are an excellent barometer of the health of Pacific Northwest waters. The recent decline in the resident orcas populations has given rise to concern regarding how man-made toxins are affecting our local orcas.

The resident orcas feed almost exclusively on salmon. Five species of salmon frequent the Pacific Northwest. Of these species, orcas prefer the chinook salmon for several reasons. First, chinook store more fat than other salmon species, and fat = energy. Second, chinook grow much larger than their cousins. Mature chinook salmon returning to Northwest waters to spawn average about 15 pounds and can grow to over 50 pounds. Third, chinook are available in local waters year round. Chinook salmon are thought to make up about 70% of the northern residents diet, and 80% of the diet for southern residents.

Unfortunately, the high fat content in chinook is a two edged sword. Although this fat is high in energy, it is also high in toxins. Persistent organic pollutants (POPs) such as PCBs (polychlorinated biphenyls) and PBDEs (polybrominated diphenylethers) collect in the fatty tissues of animals. Once consumed by a predator, those toxins become part of that predator and generally cannot be purged. The one exception is that females are able to purge some of these toxins through their breast milk as this milk is very high in fat content.

Research has established solid links between elevated levels of POPs and cancers and impaired neurological, immune system, and reproductive development. Unfortunately, much of the salmon entering Puget Sound carry three to five times higher levels of PCBs than what is considered normal. It is even worse for PBDEs - Puget Sound salmon carry four to 28 times the PDBEs of northern British Columbia salmon. Southern resident orcas feed predominately upon these salmon and bioaccumulate the toxins from these salmon in their tissues. An indicator of the ill effects of these toxins was evident in 2000 when a 22 year old male orca from J-pod washed ashore. This animal should have been sexually mature after 15 years, but was not. Toxins are believed to have impaired his maturations process and contributed to the orcas early death.

A recent study from the Canadian Department of Fisheries and Oceans indicated the following toxin levels amongst the three distinct orca communities:

*No data available for southern resident female orcas

These numbers indicate that the northern residents, which primarily forage chinook salmon from the less toxic waters of Northern Vancouver Island, only accumulated about 20% of the PCBs and less than 50% of the PBDEs than their southern cousins. This data correlates well with data analysis of local salmon toxins. Whereas Puget Sound chinook were measured to have PCB levels or around 50 parts per billion, chinook from the Johnstone Strait along northeastern Vancouver Island measure about 9 parts per billion - about 80% less. Puget Sound carries 4 to 5 times the PCB toxins of northern British Columbia.

What may seem a bit surprising is transients orcas also measure very high with regards to toxins. However, transients feed exclusively on marine mammals with high levels of fat, such as seals and porpoises. These prey animals also bioaccululate toxins from the herring, salmon, and other fish they forage. Seals from the Puget Sound region also measure very high in PCBs, PBDEs, and other toxins. Seals from Puget Sound average over twice the amount of PBDEs than their northern relatives.

The good news is PCB levels may be on the decline, albeit slow. PCBs were banned from production in the US in 1976. However contaminated waterway sediments, such as the lower Duwamish River which cuts through the heart of Seattle, continue to leach PCBs into the environment.

The news around PDBEs is less favorable. Restrictions on PDBEs were not put into place until 2006 in Washington State. PDBEs levels in salmon and other Pacific Northwest fish continue to climb. PDBEs are expected to be the most prevalent of the POPs in the near future.

In addition to PCBs and PDBEs, there are a multitude of other toxins and heavy metals that are contaminating sediments through Pacific Northwest waters - mercury, arsenic, lead, PAHs, and DDT to name but a few. The Puget Sound Partnerships study conducted by the State of Washington in 2007 concluded that about 31% of the sites surveyed in Puget Sound currently have some level of sediment degradation, with about 1% being high degraded.

Dwindling Food Supply

Toxins are only part of the problem for orcas. It is now believed that many of the resident Orcas are literally starving to death due to depleted food supplies. Most of the wild salmon runs in the Pacific Northwest are a mere fraction of what they were 30 years ago. The Columbia and Snake Rivers used to produce 10-16 million salmon annually. Runs of 1 millions are now considered a “good year”. Annual chinook runs returning to Puget Sound were guestimated to be over 1 million fish as late as the early 1970’s. The predicted forecast for returning chinook is expected to be around 222,000 fish for 2009. Many times, these estimates are overly optimistic.

The dwindling returns of salmon compound the negative impact toxins have on orcas. Orcas must use their stored body fats when food is not readily abundant. These are the same body fats laden with POPs. As these fats are consumed for energy, the POPs from the fat enter the blood stream and have an even more dire affect on the health of the orca.

Another victim from last year was a female from L-pod known as L-67. This particular orca was showing clear signs of emaciation as evidenced by the large depression behind her blow-hole just prior to her death. L-67 was not getting the food she needed to survive.

Human Harassment

Orcas rely on acoustics to find and hunt food (echo location) and communicate. Although it is illegal to approach within 100 yards of orcas in the State of Washington or put a boat intentionally in the path of an orca, a flotilla of whale watching and pleasure boats can be founding shadowing the southern residents on any summer weekend day as they hunt salmon on the south side of San Juan Island. Those of us who are scuba divers know that boat engines are very loud underwater - sound travels 4 times more efficiently through water than it does air. This constant daily auditory harassment by pleasure boats and specifically the whale watching boats has to wear on the orcas.

What Needs to Be Done - NOW

Saving orcas should not be the focus of our efforts. It should be one of the results. Orcas are a key indicator of the health of Puget Sound and Georgia Basin. We need to save these northwest waters if we want to save the orcas. We can’t save the orcas unless we save the salmon. To save the salmon, we need to save the herring and eelgrass beds in addition to protecting salmon spawning and nursery habitat. To save any of these species, we need to hold ourselves accountable and clean up our act. We are the reason Puget Sound is suffering. We are the reason the orcas are starving and so laden with toxins.

Environmental problems in Puget Sound are going to be more and more difficult to overcome. The recently downturned economy has many people more concerned about the financial well-being of their family as opposed to toxins levels and salmon restoration. Complicating matters is the fact that the Puget Sound area continues to grow. Approximately 3.6 million people resided in greater Puget Sound in 2008. In 1980, the Puget Sound region was home to only about 2.2 million people - almost 40% less. Human pressures on Puget Sound are enormous, and expected to increase.

So what can we do? Do we just let the northwest orcas and the salmon just go extinct? Do we let Puget Sound go the way of Chesapeake Bay? Absolutely not. But if we are going to make a stand and not let conditions continue to erode, we need to take dramatic actions. This means people will need to sacrifice. You will need to sacrifice. This means that businesses and industries in the Pacific Northwest will be impacted. I seriously doubt that local or federal government “officials” have the environmental consciousness to make decisions that threaten peoples jobs or way of life. Regardless, I’d like to see the following plan put in place:

1. Intensive and thoroughly clean up of derelict fishing nets and crab pots in the Pacific Northwest. Estimates are 4000 derelict fishing nets and as many as 20,000 derelict crab pots haunt Puget Sound waters alone. These nets and pots are continuous killers - especially those constructed of monofilament. Monofilament can take millennia to break down. These nets and pots trap fish and crabs, which then die. The fresh carcasses then attract and trap yet more marine life in an endless cycle. These nets and pots continually kill salmon, rockfish, seabirds, seals, crabs and other important species critical to the well-being of Puget Sound. The estimate from the Northwest Straits Foundation is it will cost about $4.5M to clean up the majority of these serial killers. The fishing and crabbing industry should be taxed to pay for this cleanup. If they can’t, they should go out of business. As the consumer ends up paying all taxes, this means increases in seafood prices.

2. Ban all fishing nets in Washington and British Columbia waters - tribal, commercial, or otherwise. Fishing nets are indiscriminant killers. Netting often results in substantial “by-catch” and the death of unintended creatures. Nets are an irresponsible way to fish. Only practices that allow selective species to be targeted and untargeted species to be safely released should be allowed. This means long-lining should be banned too.

3. Give ALL our resident marine species a break with a ten year moratorium on salt water fishing. Commercial rockfish harvesting has already been banned from Puget Sound (a bit too late, I might add). Pollutants are undoubtedly taking a heavy toll on the reproductive capabilities of all major fish stocks. Rockfish egg production has decreased by 75% in recent years. Our pollutants have put the well-being of these creatures in jeopardy - let’s not make things even more difficult by continuing to harvest these struggling species.

4. Protect the Cape Flattery area at all costs. This unique area is the last pristine sanctuary for invertebrates, rockfish, whales, sea lions, and seabirds in Washington. It needs to be protected. No development should be allowed in this area. Daily catch limits for rockfish should be reduced to a maximum of one or two fish instead of the current unsustainable limit of 10 fish daily. Better yet, eliminate all fishing from the Neah Bay area along with fishing in the rest of Washignton State and British Columbia. WDFW’s “fisheries management” practices over the last 30 years have resulted in the obliteration of many species from Puget Sound. Let’s not have a repeat performance around Washington’s last marine stronghold, Cape Flattery.

5. Hold companies ACCOUNTABLE for pollution. Boeing and Weyerhaeuser have been arguing with the EPA regarding toxins in the Duwamish Waterway for decades. Not one cent has been paid by either corporation to clean up the mess. Pollution laws and fines should be so steep that companies wouldn’t dream about dumping anything. Fines should not be equal to clean-up costs - fines should be 10 or 100 times the clean-up cost! Offending CEOs should go to jail. Heavy financial consequences and jail time are the only rules that businesses understand.

6. Don’t buy farmed fish, especially salmon! Fish pens are filthy and breed disease. Most are located along the shoreline where they end up infecting local populations of young wild fish. Farmed fish are typically much higher in toxins, hormones, and antibiotics than wild or even hatchery fish. Washington has a limited number of fish pens (currently eight), but British Columbia support an extensive fish-farming industry. Fish farming should be BANNED in the Pacific Northwest.

7. Get whale watching organizations to practice what they preach. They are very quick to report any boat that approaches too closely to orcas or other whales. However, they should know that the constant drone of the diesel engines of their whale-watching boats throughout the day is not helping either. If they really cared about the orcas, they would lobby to make the approachable limit 500 yards. But that would hurt their business.

8. Protect marine eelgrass beds and estuaries. These areas serve as the nurseries for most fish in Puget Sound, including salmon and herring. Eelgrass beds in Washington State have declined by approximately 33% so far. These areas need to be identified and declared marine preserves. Construction should not be allowed within at least one mile of these critical areas.

9.Zero population growth. One of these days, we need to WAKE UP and realize that more people on this already overcrowded planet is not a good thing. We are quickly consuming this planet, forcing out species, and altering the Earth’s climate. Some estimates are that half the world’s species will be extinct within the next 100 years due to human pressures on the planet. We need to live in equilibrium with nature, not destroy it. However, as long as certain religions blindly preach large families and governments give tax breaks for having more and more children, I fear populations will continue to increase well beyond the point where our planet can support us. I truly fear the legacy of environmental, resource, and now financial problems you and I are leaving for our kids.

Who is killing our local orcas? You and I, and everyone else who passively supports our current way of life.

References:

PERSISTENT ORGANIC POLLUTANTS IN CHINOOK SALMON (ONCORHYNCHUS TSHAWYTSCHA): IMPLICATIONS FOR RESIDENT KILLER WHALES OF BRITISH COLUMBIA AND ADJACENT WATERS (O’neil et al., 2008)

Recovery Plan for Southern Resident Killer Whales (Orcinus orca) (National Marine Fisheries Service

Northwest Regional Office, 2008)

State of the Sound 2007 (Puget Sound Action Team, 2007)

Toxins in Harbor Seals (US EPA, 2006) http://www.epa.gov/r10earth/psgb/indicators/harbor_seals/what/index.htm

The Northwest Straits Foundation Derelict Fishing Gear Removal Program

These numbers indicate that the northern residents, which primarily forage chinook salmon from the less toxic waters of Northern Vancouver Island, only accumulated about 20% of the PCBs and less than 50% of the PBDEs than their southern cousins. This data correlates well with data analysis of local salmon toxins. Whereas Puget Sound chinook were measured to have PCB levels or around 50 parts per billion, chinook from the Johnstone Strait along northeastern Vancouver Island measure about 9 parts per billion - about 80% less. Puget Sound carries 4 to 5 times the PCB toxins of northern British Columbia.

What may seem a bit surprising is transients orcas also measure very high with regards to toxins. However, transients feed exclusively on marine mammals with high levels of fat, such as seals and porpoises. These prey animals also bioaccululate toxins from the herring, salmon, and other fish they forage. Seals from the Puget Sound region also measure very high in PCBs, PBDEs, and other toxins. Seals from Puget Sound average over twice the amount of PBDEs than their northern relatives.

The good news is PCB levels may be on the decline, albeit slow. PCBs were banned from production in the US in 1976. However contaminated waterway sediments, such as the lower Duwamish River which cuts through the heart of Seattle, continue to leach PCBs into the environment.

The news around PDBEs is less favorable. Restrictions on PDBEs were not put into place until 2006 in Washington State. PDBEs levels in salmon and other Pacific Northwest fish continue to climb. PDBEs are expected to be the most prevalent of the POPs in the near future.

In addition to PCBs and PDBEs, there are a multitude of other toxins and heavy metals that are contaminating sediments through Pacific Northwest waters - mercury, arsenic, lead, PAHs, and DDT to name but a few. The Puget Sound Partnerships study conducted by the State of Washington in 2007 concluded that about 31% of the sites surveyed in Puget Sound currently have some level of sediment degradation, with about 1% being high degraded.

Dwindling Food Supply

Toxins are only part of the problem for orcas. It is now believed that many of the resident Orcas are literally starving to death due to depleted food supplies. Most of the wild salmon runs in the Pacific Northwest are a mere fraction of what they were 30 years ago. The Columbia and Snake Rivers used to produce 10-16 million salmon annually. Runs of 1 millions are now considered a “good year”. Annual chinook runs returning to Puget Sound were guestimated to be over 1 million fish as late as the early 1970’s. The predicted forecast for returning chinook is expected to be around 222,000 fish for 2009. Many times, these estimates are overly optimistic.

The dwindling returns of salmon compound the negative impact toxins have on orcas. Orcas must use their stored body fats when food is not readily abundant. These are the same body fats laden with POPs. As these fats are consumed for energy, the POPs from the fat enter the blood stream and have an even more dire affect on the health of the orca.

Another victim from last year was a female from L-pod known as L-67. This particular orca was showing clear signs of emaciation as evidenced by the large depression behind her blow-hole just prior to her death. L-67 was not getting the food she needed to survive.

Human Harassment

Orcas rely on acoustics to find and hunt food (echo location) and communicate. Although it is illegal to approach within 100 yards of orcas in the State of Washington or put a boat intentionally in the path of an orca, a flotilla of whale watching and pleasure boats can be founding shadowing the southern residents on any summer weekend day as they hunt salmon on the south side of San Juan Island. Those of us who are scuba divers know that boat engines are very loud underwater - sound travels 4 times more efficiently through water than it does air. This constant daily auditory harassment by pleasure boats and specifically the whale watching boats has to wear on the orcas.

What Needs to Be Done - NOW

Saving orcas should not be the focus of our efforts. It should be one of the results. Orcas are a key indicator of the health of Puget Sound and Georgia Basin. We need to save these northwest waters if we want to save the orcas. We can’t save the orcas unless we save the salmon. To save the salmon, we need to save the herring and eelgrass beds in addition to protecting salmon spawning and nursery habitat. To save any of these species, we need to hold ourselves accountable and clean up our act. We are the reason Puget Sound is suffering. We are the reason the orcas are starving and so laden with toxins.

Environmental problems in Puget Sound are going to be more and more difficult to overcome. The recently downturned economy has many people more concerned about the financial well-being of their family as opposed to toxins levels and salmon restoration. Complicating matters is the fact that the Puget Sound area continues to grow. Approximately 3.6 million people resided in greater Puget Sound in 2008. In 1980, the Puget Sound region was home to only about 2.2 million people - almost 40% less. Human pressures on Puget Sound are enormous, and expected to increase.

So what can we do? Do we just let the northwest orcas and the salmon just go extinct? Do we let Puget Sound go the way of Chesapeake Bay? Absolutely not. But if we are going to make a stand and not let conditions continue to erode, we need to take dramatic actions. This means people will need to sacrifice. You will need to sacrifice. This means that businesses and industries in the Pacific Northwest will be impacted. I seriously doubt that local or federal government “officials” have the environmental consciousness to make decisions that threaten peoples jobs or way of life. Regardless, I’d like to see the following plan put in place:

1. Intensive and thoroughly clean up of derelict fishing nets and crab pots in the Pacific Northwest. Estimates are 4000 derelict fishing nets and as many as 20,000 derelict crab pots haunt Puget Sound waters alone. These nets and pots are continuous killers - especially those constructed of monofilament. Monofilament can take millennia to break down. These nets and pots trap fish and crabs, which then die. The fresh carcasses then attract and trap yet more marine life in an endless cycle. These nets and pots continually kill salmon, rockfish, seabirds, seals, crabs and other important species critical to the well-being of Puget Sound. The estimate from the Northwest Straits Foundation is it will cost about $4.5M to clean up the majority of these serial killers. The fishing and crabbing industry should be taxed to pay for this cleanup. If they can’t, they should go out of business. As the consumer ends up paying all taxes, this means increases in seafood prices.

2. Ban all fishing nets in Washington and British Columbia waters - tribal, commercial, or otherwise. Fishing nets are indiscriminant killers. Netting often results in substantial “by-catch” and the death of unintended creatures. Nets are an irresponsible way to fish. Only practices that allow selective species to be targeted and untargeted species to be safely released should be allowed. This means long-lining should be banned too.

3. Give ALL our resident marine species a break with a ten year moratorium on salt water fishing. Commercial rockfish harvesting has already been banned from Puget Sound (a bit too late, I might add). Pollutants are undoubtedly taking a heavy toll on the reproductive capabilities of all major fish stocks. Rockfish egg production has decreased by 75% in recent years. Our pollutants have put the well-being of these creatures in jeopardy - let’s not make things even more difficult by continuing to harvest these struggling species.

4. Protect the Cape Flattery area at all costs. This unique area is the last pristine sanctuary for invertebrates, rockfish, whales, sea lions, and seabirds in Washington. It needs to be protected. No development should be allowed in this area. Daily catch limits for rockfish should be reduced to a maximum of one or two fish instead of the current unsustainable limit of 10 fish daily. Better yet, eliminate all fishing from the Neah Bay area along with fishing in the rest of Washignton State and British Columbia. WDFW’s “fisheries management” practices over the last 30 years have resulted in the obliteration of many species from Puget Sound. Let’s not have a repeat performance around Washington’s last marine stronghold, Cape Flattery.

5. Hold companies ACCOUNTABLE for pollution. Boeing and Weyerhaeuser have been arguing with the EPA regarding toxins in the Duwamish Waterway for decades. Not one cent has been paid by either corporation to clean up the mess. Pollution laws and fines should be so steep that companies wouldn’t dream about dumping anything. Fines should not be equal to clean-up costs - fines should be 10 or 100 times the clean-up cost! Offending CEOs should go to jail. Heavy financial consequences and jail time are the only rules that businesses understand.

6. Don’t buy farmed fish, especially salmon! Fish pens are filthy and breed disease. Most are located along the shoreline where they end up infecting local populations of young wild fish. Farmed fish are typically much higher in toxins, hormones, and antibiotics than wild or even hatchery fish. Washington has a limited number of fish pens (currently eight), but British Columbia support an extensive fish-farming industry. Fish farming should be BANNED in the Pacific Northwest.

7. Get whale watching organizations to practice what they preach. They are very quick to report any boat that approaches too closely to orcas or other whales. However, they should know that the constant drone of the diesel engines of their whale-watching boats throughout the day is not helping either. If they really cared about the orcas, they would lobby to make the approachable limit 500 yards. But that would hurt their business.

8. Protect marine eelgrass beds and estuaries. These areas serve as the nurseries for most fish in Puget Sound, including salmon and herring. Eelgrass beds in Washington State have declined by approximately 33% so far. These areas need to be identified and declared marine preserves. Construction should not be allowed within at least one mile of these critical areas.

9.Zero population growth. One of these days, we need to WAKE UP and realize that more people on this already overcrowded planet is not a good thing. We are quickly consuming this planet, forcing out species, and altering the Earth’s climate. Some estimates are that half the world’s species will be extinct within the next 100 years due to human pressures on the planet. We need to live in equilibrium with nature, not destroy it. However, as long as certain religions blindly preach large families and governments give tax breaks for having more and more children, I fear populations will continue to increase well beyond the point where our planet can support us. I truly fear the legacy of environmental, resource, and now financial problems you and I are leaving for our kids.

Who is killing our local orcas? You and I, and everyone else who passively supports our current way of life.

References:

PERSISTENT ORGANIC POLLUTANTS IN CHINOOK SALMON (ONCORHYNCHUS TSHAWYTSCHA): IMPLICATIONS FOR RESIDENT KILLER WHALES OF BRITISH COLUMBIA AND ADJACENT WATERS (O’neil et al., 2008)

Recovery Plan for Southern Resident Killer Whales (Orcinus orca) (National Marine Fisheries Service

Northwest Regional Office, 2008)

State of the Sound 2007 (Puget Sound Action Team, 2007)

Toxins in Harbor Seals (US EPA, 2006) http://www.epa.gov/r10earth/psgb/indicators/harbor_seals/what/index.htm

The Northwest Straits Foundation Derelict Fishing Gear Removal Program